Audrey Woods, MIT CSAIL Alliances | December 8, 2025

Most robotic systems so far have been designed with a position-centric view of manipulation and interaction. Robot algorithms were written to direct the machine precisely where in space to move, grab, step, climb, or walk. However, MIT CSAIL Associate Professor Pulkit Agrawal argues that’s not how humans learn and act. “Really, manipulation—the way we interact with the physical world—is through forces.”

As the leader of the Improbable AI Lab, Professor Agrawal is applying force-centric thinking to robotic manipulation to tackle some of the hardest problems in robotics, especially dexterity and training via simulation. Inspired by human intelligence and motivated by how robots could make millions of lives better, he is leading a paradigm shift in the field and creating a new future for robotic manipulation.

APPLYING HUMAN INTELLIGENCE TO MACHINE MOVEMENT

Professor Agrawal didn’t set out to be a computer scientist. In fact, he “didn’t like the concept of programming” and was instead fascinated by the human brain. He studied electrical engineering to better understand the mechanism of neurons and the “small electric circuits” inside and between them, but soon realized that “just understanding electric circuits tells you how the circuit works, not what the system is doing.” He wanted to understand the algorithms of the brain, the systemic mechanisms being implemented to understand intelligence and thought. “It turned out that discipline was called artificial intelligence, and a lot of the AI people were computer scientists. So that’s why I got into computer science.”

Initially, Professor Agrawal was in the computer vision space, starting with an internship studying a medical condition called Rosacea, which makes the skin red and irritated. At the time, he was trying to find an “absolute truth” for how to define redness, since diagnosing the disease was quite subjective. But, after working in computer vision for a few years, he wanted to return to his original mission of understanding and replicating human cognition. In computer vision, learning is centered around annotated images and giant datasets. But that’s not how people learn. “As a human, if you don’t understand something, you try to change it or take some other action or find more information. There’s this active element that you’re seeking more information and acting in the world.” When looking for a system he could study that would bring in that active element, he says, “robots are a mechanism where an agent can decide when to act in the world, then collect that information and, based on that information, decide again what to do. That would be closer to the kind of intelligence humans have.” Besides, “robots are cool.”

Now, as he pushes the boundaries of dexterous robotic manipulation, Professor Agrawal is motivated by the good robots might do in the world. “It’s not just that you would have a cool piece of technology, but think about the impact it can have with the aging we are seeing in the world, the labor shortages, and the fact that there are so many people doing things they really don’t want to do.” Hard physical work in dangerous environments all over the world could be done by machines, which, at the same time, could enhance our understanding of human intelligence. “These two reasons are what make me excited about robotics.”

A SHIFT TOWARD MACHINE LEARNING AND FORCE-CENTRIC MANIPULATION

One of the biggest changes in robotics that Professor Agrawal has seen is the shift in mindset from requiring precise, granular instructions for a robot to the concept of letting them learn how to perform a task through data and simulation. “Pre-2018, the mainstream view was that learning has little role to play in robotics,” Professor Agrawal explains, “but now the field has completely changed where the mainstream view has become that we should not spend our time writing how a robot should do task one, task two, task three, etc., but we want to give the robot data and have it autonomously figure out the task that needs to be done.”

With this change, CEOs and manufacturing leaders are asking, “When will we have a ChatGPT moment in the physical world?” There’s widespread interest in humanoid robots which could embody the kind of intelligence unfolding in the LLM space, but Professor Agrawal thinks this is overlooking “the hardest problem,” which in his mind is robot hands. “Getting to human-level manipulation—what we call dexterous manipulation—is, in my opinion, the biggest challenge.” With billions of dollars flowing through human hands every day, unlocking the potential of humanlike manipulation is the key to widespread adoption and value.

So what’s missing? Professor Agrawal believes progress will be found in a combination of algorithms and hardware that better replicate the actual sensation of human touch. “If you look at the human hand, it has this element of a high-dimensional control problem.” In this area, Professor Agrawal believes roboticists have been pursuing the wrong thing with position-centric views of manipulation. “If I want to move something, I have to apply a force. No one says to apply a position, right?” To think about what it means to pick up an object, he challenges people to imagine quickly picking something off a table. It’s very difficult to do this without the soft pads of your fingers touching the table, feeling the forces of the material push back, and judging how hard to press based on that. His group is therefore taking a “force-centric view of manipulation, saying that forces are the language of manipulation.”

His group is also leveraging simulation as a training medium for robots. It’s classically difficult to get enough physical-world data to accurately train machines, but simulators can replicate the laws of physics and allow programmers to train their algorithms in force-rich environments at scale. “As we tie our hardware built with a force-centric philosophy with data from simulation, we could start moving toward foundational models for manipulation.”

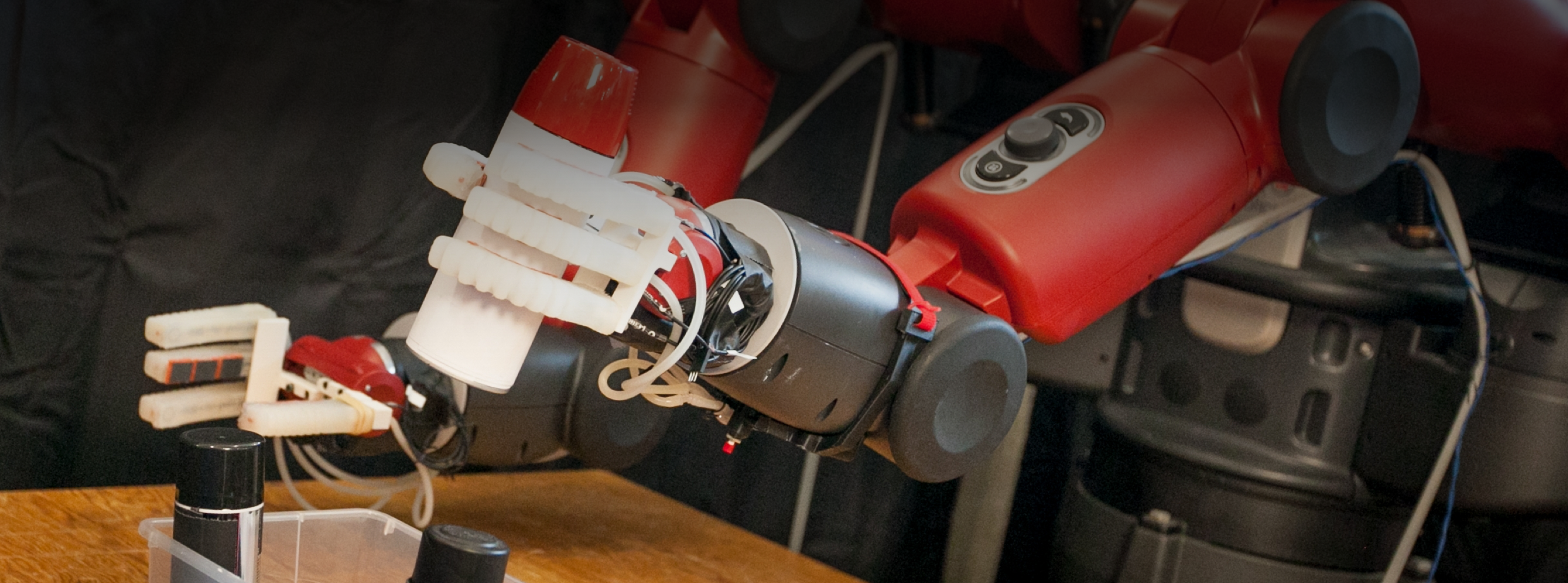

In practice, Professor Agrawal’s research group is testing their ideas with prototypes like DexWrist, a robotic wrist which mimics the kinematics of the human wrist, robotic hands and robotic data collection mechanism (DEXOP) wrapped with a sense of touch, “RialTo”, a framework for creating "digital twin" simulations real-world capture of scenes from user phones, leveraging large scale simulation for tackling some of the most challenging dexterous manipulation problems such as object re-orientation, and self-learning AI models like SEAL, which can generate its own training data and self-edit through supervised fine-tuning. Together, these approaches offer new and exciting ways to explore what’s possible with robots and AI models.

LEARNING ROBOTS, CSAIL ALLIANCES, AND FUTURE WORK

Professor Agrawal is currently helping build a new theme under the CSAIL Alliances Research Initiative MachineLearningApplications@CSAIL to focus on Learning Robots, which he will lead as Faculty Director. “The main message is that there is a shift that is happening in how we approach robotics. There are problems that people thought were impossible to solve with robots, and those problems are now being solved with robots. If you want to participate in shaping the future of how robots and machine learning will come together to redefine the future of the workplace in the physical world, this is your chance to be a part of this initiative.” He hopes this MLA@CSAIL theme will be a “playground of ideas,” where companies and MIT faculty from all across campus can come together and define what the field can accomplish in the next 5-10 years. Will there be humanoids in factories? Will there be robot butlers in homes? What will robot-human interaction look like as robots emerge in the market? “I want to be holistic in this space, where anything touching robotics and machine learning is welcome.”

For Professor Agrawal, CSAIL Alliances offers insight into the grounded problems companies are facing. He emphasizes how helpful it is “talking to companies to understand their needs and how they’re thinking about things in the future, even co-creating what that vision might look like.” He urges companies to lay out their problems and pain points, perhaps even presenting them to researchers like him through CSAIL Alliances, since getting to the “core of machine learning problems, tying them back into a product, and thinking at the product or capacity level about what is missing would be great.”

Going forward, there are many hurdles to overcome before robots can perform tasks that are even remotely comparable to the everyday manipulations we undertake all the time. Professor Agrawal believes there won’t be one big, flashy moment the way there was with ChatGPT, but a progression of technology getting better, things slowly becoming more automated, and, eventually, a future of widely-integrated and effective robots. With smarter algorithms, better hardware, and new ways of thinking, Professor Agrawal is leading the way to that future.

Learn more about Professor Agrawal on his website or CSAIL page.