Audrey Woods | MIT CSAIL Alliances

MIT CSAIL Assistant Professor Andreea Bobu has known she wanted to study computer science since she was in second grade. As a child in Romania, Professor Bobu was a member of the Informatics Club, a government-sponsored educational program for young students interested in computers and technology, where she created a computer loop to add up thousands of numbers almost instantaneously. “It would have taken me so much longer,” a young Professor Bobu realized. This experience gave her a visceral feeling of what technology might be capable of, that “we can actually use this to make people's lives so much easier” both by taking on menial tasks people don’t want to do and by augmenting human performance in important and meaningful work.

Guided by this mission, Professor Bobu came to MIT as an undergraduate to figure out how to make lives easier. At first, she was drawn to AI, probability, and inference style courses, doing a UROP (Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program) in medical imaging which gave her experience extracting useful information out of limited hospital data. She says, “ the only exposure I had to robotics was [Professors] Nick Roy and Sertac Karaman’s Intro to Robotics course.” Though she began her PhD working in computer vision, Professor Bobu found herself seeking different challenges that aligned more closely with her interests in human-centered applications.

Switching directions, Professor Bobu began working on human robot interaction, which she found was quite similar to the medical imaging work she’d enjoyed in her UROP. In robotics, “we have sparse data from people. We only get this many points of interaction with people or from people because it’s expensive to ask for human data.” This created a core problem: “how do you gain a lot of information from sparse data to build a tool that helps people?”

Now, as an Assistant Professor at CSAIL, Professor Bobu leads the Collaborative Learning and Autonomy Research (CLEAR) Lab where she continues to pursue her goal of creating tools, algorithms, and agents that can augment human performance and help people in their everyday tasks. In a fun full-circle moment, Professor Bobu is currently teaching an Introduction to Autonomy and Decision-Making course with Professor Nick Roy.

PROFESSOR BOBU’S RESEARCH: GETTING ROBOTS TO LEARN FROM PEOPLE

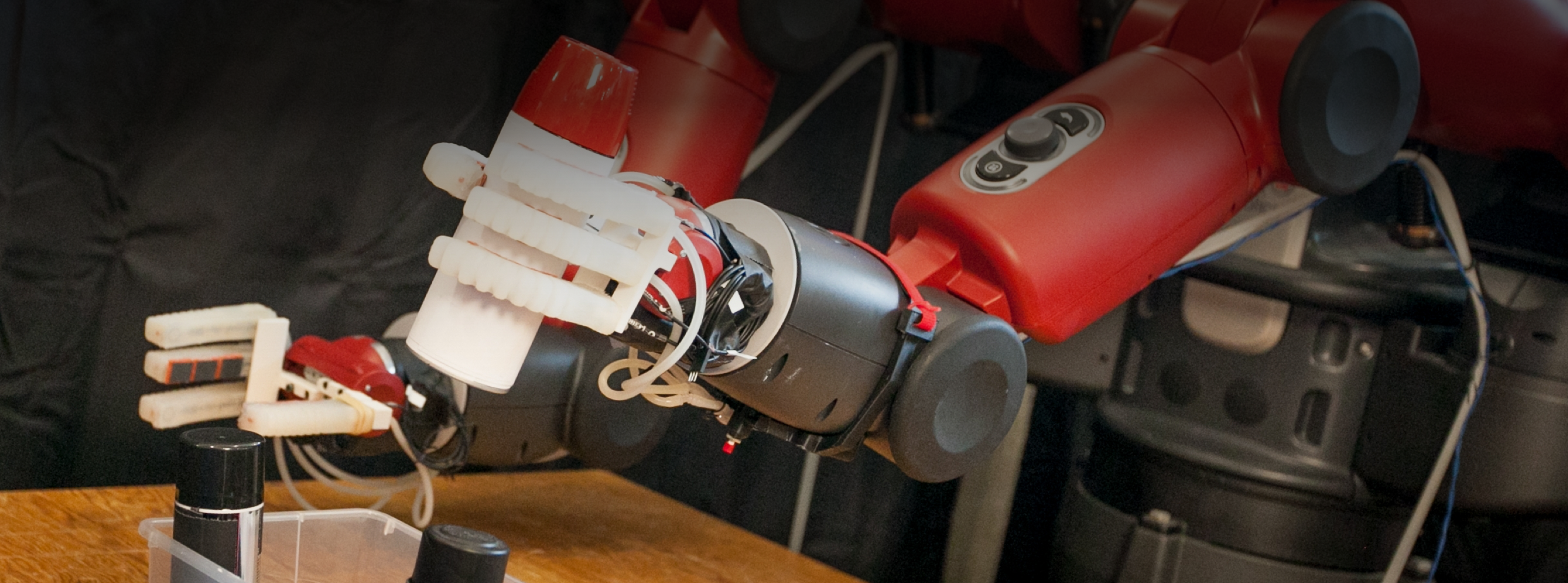

A central problem of robotics research is a lack of data. The explosion seen in LLMs and Generative AI is due largely to the fact that there is a whole internet full of language data to draw on for training. But there is no such resource for movement and physical tasks. Professor Bobu says “the Holy Grail [of robot learning] is having a generalist robot that can do a lot of different tasks for the person in a home. So how do we get robots to learn all of these things?” Currently, researchers collect demonstrations to train a robot at a specific task by physically moving the robot or using teleoperation. But Professor Bobu believes such methods are “inefficient for a variety of reasons,” chiefly that demonstrations only train for a very specific version of a task (i.e. picking up a mug of a certain color or shape). In order to create robots that can truly adapt to peoples’ homes and preferences—such as how they prefer to load a dishwasher—Professor Bobu “finds it hard to believe that we can capture so many different environment types and human particularities just by collecting demonstrations in a factory.”

Professor Bobu is exploring how to collect useful human data. “Humans aren’t infinitely queryable. They’re fallible, they have limited attention spans, limited patience.” When training a theoretical house robot out of the box, “giving a demonstration is actually quite challenging for someone who is not an expert.” Finding out what kinds of data can be gathered from humans—and how to make the most out of that information—is a key open question in the pursuit of general robot intelligence.

To fill these gaps, Professor Bobu is studying a few different methods. One is augmenting robot understanding with large language models. “LLMs are super useful because they have this repository of knowledge that I don’t need to query the human for, but rather there are several pieces of human knowledge that I can get for free from the LLM.” Speaking on the CSAIL Alliances Podcast, Professor Bobu elaborates that LLMs are capable of breaking large tasks down into smaller tasks, which would be a critical component of general-function robots. “LLMs themselves can chain the sequence of commands and know what the robot is supposed to do. So now all the robot needs to know is how to ground these commands into actions.” Also, adding LLMs to robot interfaces will make them more approachable to casual users, allowing people to “speak” to their robot in common language without needing coding experience or specific training, and might even allow them to respond emotionally to a situation depending on the user’s mood.

A related approach that Professor Bobu’s group is pursuing is training via simulation, where a human can give one physical demonstration of a given task and then the robot can be trained hundreds of times via simulation with minor modifications. “Then I get a bunch of data for free. I don’t need to query the person multiple times.” Language or video generative models can be useful here as well—when given the core element of a task, they can generate many digital versions of the same task, tweaking elements like the background or shape to give the robot a more robust understanding of the scenario.

The third core aspect of Professor Bobu’s research is representation, or studying how a human represents a problem versus how a robot represents a problem. “It’s very important that they’re aligned, otherwise the robot is not going to be able to understand the human properly.” For example, it’s critical for a robot to understand the non-negotiable aspects of a task, like not spilling coffee on a computer or book. Furthermore, in real-world applications these non-negotiable aspects might be specific to certain individuals. Some users might be scared by the robot moving too fast or too close to their face, while others might care more about getting a task done quickly and efficiently. This work builds on the foundation of Professor Bobu’s PhD Thesis, “Aligning Robot Representations with Humans,” which argued that scientists “should treat humans as active participants in the interaction, not as static data sources.”

Broadly, Professor Bobu sums up the state of robotics research in her 2024 TED talk, saying “we are the problem. Humans. We are the Kryptonite to our robots.” While robots perform beautifully in closed environments interacting only with other machines, it’s out in the real world where they struggle. Autonomous cars face the challenge of human drivers and pedestrians; Roombas must adjust to shoes, toys, and changing furniture arrangements. “Humans introduce a lot of uncertainty and uncontrollable variables,” Professor Bobu says, so the current question of robotics—one she’s working hard to address—is how to create machines that can interact seamlessly, safely, and productively in dynamic human environments.

LOOKING AHEAD: A MESSAGE TO INDUSTRY

What does Professor Bobu think businesses need to understand about robotics? “I really wish more people remembered that humans are not machines. Because we as humans are imperfect, messy, and biased, I don’t think we should treat human data as coming from an oracle.” This is true not just in robotics but in all machine learning algorithms and systems, where engineers might take data and not question where it came from or how it was collected. Data created or labeled by humans is “going to have a lot of mistakes, a lot of inconsistencies. So it’s super important to think about how we can make it easier for people to give higher quality data.” Maybe this means changing how data is collected, offering better interfaces or more intuitive methods. Or perhaps there’s a way to clean up existing data and make it more useful. Either way, the fundamental problem remains: “how do we instill human knowledge into a robot?”

Professor Bobu is inspired by the incredible technological progress she’s seen in the course of her career. “We’re starting to have self-driving cars driving around, at least in Phoenix and San Francisco, which is mind blowing,” something she never thought she’d see as a child. More than that, LLMs are becoming integrated into society, accessible in ways that they’ve never been before, and that is inspiring non-experts to use technology in their daily lives in a way that’s “super exciting to see.”

As Professor Bobu works toward creating all-purpose robots which could eliminate dreary everyday tasks and expand the capacity of people across specialties, she urges us to keep in mind “that humans are imperfect. Our data is imperfect, but our data is what powers all of these algorithms, so our algorithms will be imperfect.” But that doesn’t mean that they can’t make a world of difference.

To learn more about Professor Bobu’s research, visit her website or CSAIL page.