Audrey Woods, MIT CSAIL Alliances | December 15, 2025

When most people think of 3D printing, they imagine static objects—plastic prototypes, replacement parts, maybe even art pieces. But MIT CSAIL postdoctoral fellow Jiaji Li envisions something far more dynamic: printing movement itself.

By designing methods that embed strings, tendons, and other biological analogs directly into printed objects, Dr. Li is creating mechanisms that can bend, grasp, and even sense without the painstaking manual labor usually required to thread cables or install sensors. For him, every print is a chance to bring a new mechanism to life.

ARCHITECTURE TO 3D PRINTING: AUTOMATING DESIGN

Dr. Li originally majored in architecture, but was quickly drawn to digital fabrication because he wanted to address the huge amount of repetitive work and details that went into architecture design. “I wanted to do something more automatic and make the design process simpler.” He switched to studying Digital Art and Design, specifically the fabrication area of Human Computer Interaction (HCI), where he could work on tangible interfaces and parametric design tools. Ultimately, he wanted to create one-step fabrication tools that would streamline the whole design and fabrication process.

This goal brought him to the lab of MIT CSAIL Associate Professor Stefanie Mueller, a famous researcher in the HCI world. After graduating with his PhD, he approached her because “her group is building all kinds of different interactive ways in the physical world to do HCI. That’s basically my interest, and it aligns perfectly with her work.”

RESEARCH: 3D PRINTING DYNAMIC OBJECTS INSPIRED BY BIOLOGY

Before coming to MIT, Dr. Li worked on a variety of systems that could design and print kinematic mechanisms, or a system of connected pieces designed to produce controlled motion. He was involved in creating X-Bridges—a design workflow that lets novice users create 3D-printed “bridges” with tunable flexibility, enabling objects that can bend, twist, compress, and transform into interactive, shape-changing forms—and later X-Hair—a 3D printing method and design tool that lets users generate customizable hair-like structures with different forms and properties, enabling applications from biomimicry to decoration and haptic interaction.

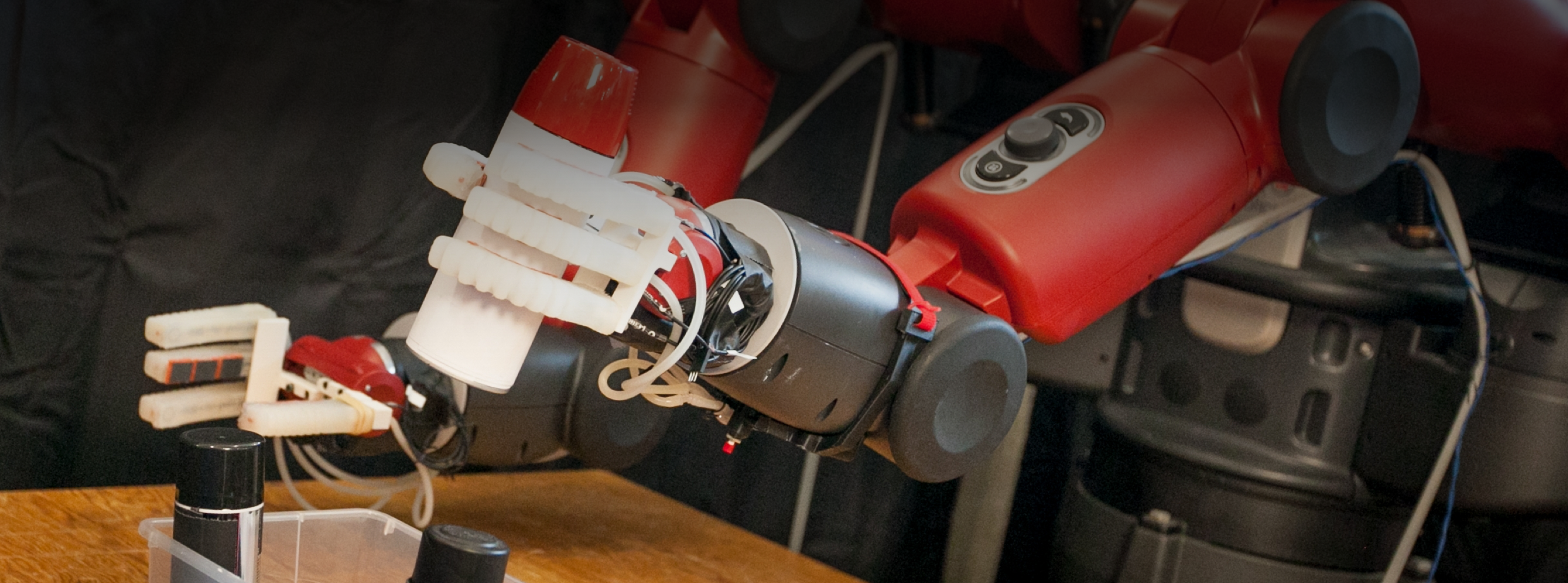

In early 2025, Dr. Li and his colleagues in Professor Mueller’s lab presented Xstrings, a one-step 3D printing method and design tool that embeds cable-driven mechanisms directly into objects, enabling dynamic interactions like bending, coiling, screwing, and compressing without manual assembly. This system could dramatically accelerate the process of creating, for example, robotic hands or gripping tools. “Xstrings is a fabrication method that relieves human labor in the assembly of cable-driven mechanisms in robotics,” Dr. Li explains. “If you try to assemble string-actuated robots, it’s hard because you have to manually thread a cable through dozens of holes and make sure the tension is precise. It’s a lot of manual work. Our method is just one step with the same quality and zero human labor.”

The paper received a Best Paper Honorable Mention at CHI 2025 and was widely covered by ACM Tech, MIT Daily, and numerous other 3D printing websites. This research shows exciting potential in many fields, including personalized prosthetics, soft robotics, interactive interfaces, wearable electronics, educational tools, and even kinetic art. In these scenarios, designers can rapidly create flexible, responsive, and shape-changing objects. Currently, Dr. Li is further expanding this research by incorporating conductive materials into the 3D printing process, enabling printed objects to gain sensing capabilities and paving the way for digital twins that respond to real-world input.

LOOKING AHEAD: OPPORTUNITIES & EXCITEMENT

Dr. Li sees endless opportunities in the world of 3D printing. Imagine being able to manufacture low-cost prototypes rapidly with customized shapes, or print entirely personalized HCI controllers to replace a computer keyboard or mouse. He believes the controllers of the future will be “more vivid and biometric” in a way that relates to whatever the user is doing, like gaming or designing. “This kind of customization which could fabricate for your personal use the shape you want is a huge contribution from the HCI Engineering lab.”

With wide-ranging interests and a passion for working on many different projects at once, Dr. Li hopes to stay in academia. “I want to explore new things,” he says, comparing the process of 3D printing to parenting. “Each cycle of redesign and reprinting feels like watching something evolve. With every iteration, the object becomes smarter, more dynamic and more sophisticated. That sense of seeing something evolve is a big passion of mine.” He's also motivated by the joy of sharing new methods and approaches with the academic community, adding, “that’s why I wake up every day.”

In the future, he sees 3D printing becoming increasingly complicated, enabling actuation and sensing in a way that will not only allow for more complex designs but will also make things cheaper and more accessible. “With a 3D printer, you can customize and fabricate in one step, which will be really helpful to industrial manufacturers.”

Dr. Li’s vision reflects a future where fabrication is not just about creating objects but about imbuing them with motion, adaptability, and intelligence. By simplifying the design process and embedding dynamic capabilities directly into the print itself, his work has the potential to transform how we manufacture, use, and interact with technology.

3D-Printed Tendons = Precise Robotics 🧵🤖

3D-Printed Creatures That Move Like Nature 🦎🦾✨

Learn more about Dr. Li on his website or LinkedIn Page.